The NOAA Deep Sea Coral Research and Technology Program has completed two research initiatives in Alaska. The first initiative (2012–2015) expanded our knowledge of coral and sponge communities in Alaska’s waters through extensive visual surveys, modeling, and several targeted studies. This research included a vastly increased understanding of red tree corals—large and ecologically important structure-forming organisms. The second initiative (2020–2024) built upon previous research in Alaska’s waters to produce data to inform effective natural resource management. Between initiative years, ongoing projects in the region have supported conservation efforts.

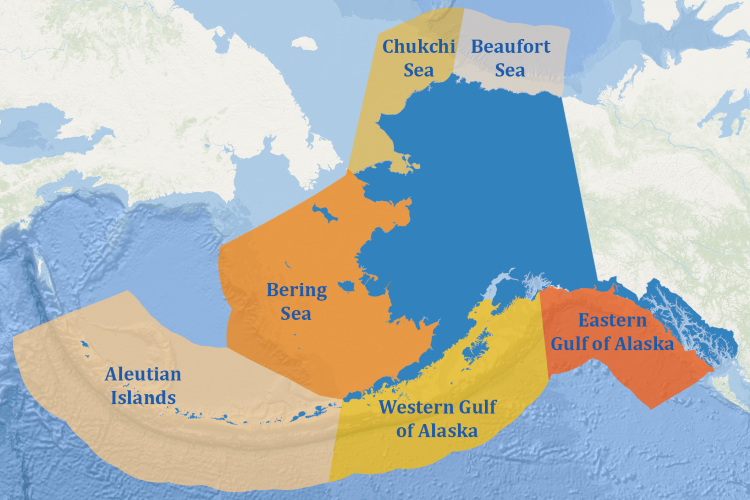

The U.S. waters surrounding Alaska encompass six distinct regions that reflect the unique flora and fauna of each area: the Beaufort Sea, the Chukchi Sea, the Bering Sea, the Aleutian Islands, the western Gulf of Alaska, and the eastern Gulf of Alaska.

The region contains more than 70 percent of the United State’s continental shelf, supports some of the nation’s most productive fisheries, and is home to a rich biological diversity of deep-sea corals and sponges. These organisms can live for hundreds or thousands of years, contributing to productive habitats that support complex communities, including commercially important fish and invertebrates. Nearly 150 species of corals and over 200 species of sponges are found in Alaska’s rich marine waters. In particular, the Aleutian Islands has some of the densest and most diverse coral and sponge communities in the world. However, the full geographic extent of these habitats is still unknown as vast areas of the region have yet to be explored.

Additionally, some Alaska corals and sponges have direct benefits beyond supporting local fisheries. For example, in 2005, a NOAA Fisheries research scientist discovered a green sponge (Latrunculia austini) that creates compounds with potential for use in cancer treatment. Therefore, investments in deep-sea coral and sponge research and exploration in Alaska may result in a variety of societal benefits beyond fish habitat.

Globally, commercial bottom-contact fishing (PDF, 481 pages; Chapter: 20 pages), particularly certain bottom trawl fisheries in unprotected areas, presents the most serious threat to deep-sea coral and sponge habitat. In response, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council has taken actions to protect seafloor habitats in Alaska’s waters from damage caused by fishing gear. For example, in 2005 the council adopted the Aleutian Islands Habitat Conservation Area, which protects nearly 960,000 square kilometers (370,000 square miles; an area roughly two and a half times the size of Montana) of seafloor from bottom trawling. They also prohibited commercial fishing in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas in 2009. This precautionary but non-permanent decision later fed into a larger 2018 international moratorium on fishing in the North Arctic.

The treaty bars unregulated fishing in the high seas of the central Arctic Ocean for at least 16 years. The moratorium is intended to give scientists ample time to study and monitor fisheries in the Arctic to determine if commercial fishing can be sustainably conducted in this region.

To learn more about these protections, see Chapter 3 of the Program’s 2017 report: “The State of Deep‐Sea Coral and Sponge Ecosystems of the United States” (PDF, 481 pages; Chapter: 37 pages) or explore our story map about Deep-Sea Coral Protection in U.S. Waters.

In 2022 and 2023, researchers embarked on expeditions to survey, sample, and map deep-sea coral and sponge ecosystems in Alaska’s waters. This fieldwork was complemented by a series of smaller targeted research projects, ranging from environmental DNA studies of fish and corals, to refining estimates of longline and pot fishing gear interactions with corals and sponges. Learn more by reading the initiative science plan (PDF, 53 pages).

Initiative Highlights

Research from the current Alaska initiative is supporting the goal of better understanding deep-sea coral and sponge ecosystems. This work is building on findings from the first initiative and subsequent research. Major initiative project objectives include the following:

- Validating Gulf of Alaska coral and sponge distribution models

- Studying recruitment, reproduction, and early life history of Alaskan corals and sponges to better understand their ecology, diversity, genetic connectivity, and taxonomy

- Assessing the effectiveness of Aleutian Islands area closures in maintaining healthy coral and sponge communities

- Exploring seamounts in the eastern North Pacific Ocean through a collaborative effort between the U.S. and Canada

- Monitoring the effects of climate change and ocean acidification on deep-sea corals and sponges

The initiative is also part of Seascape Alaska, a regional campaign to support the 2020 National Strategy for Mapping, Exploring, and Characterizing the United States Exclusive Economic Zone. The campaign is a collaboration among federal, tribal, state, and non-governmental partners with a wide range of interests and needs for mapping data across U.S. coastal and ocean waters.

Prior to 2012, NOAA had funded few major fieldwork efforts in Alaska’s waters. Researchers conducted several small projects, focused mostly on biological processes, with limited funding from various sources. Much of what we have learned about deep-sea corals and sponges in Alaska since 2012 is the result of Program-funded research projects developed in consultation with the North Pacific Fishery Management Council and led by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

The regionally-led initiative included mapping and surveys to understand the spatial distribution of deep-sea coral and sponge habitats, with projects on the following:

- Understanding life histories of these organisms and their contributions to biodiversity

- Developing habitat suitability models—or predicted occurrences of species

- Assessing the impact of human activities on deep-sea corals and sponges

Initiative Highlights

During the first Alaska initiative, the Program and partners accomplished several major goals and produced important findings, including the following:

- Developing new maps predicting the occurrence and abundance of corals and sponges for the Gulf of Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, and the eastern Bering Sea.

- Completing the first comprehensive visual surveys of corals and sponges in the Aleutian Islands and the eastern Bering Sea slope and outer shelf from Bering Canyon in the south to Pervenets Canyon in the north.

- Discovering 47 new high-density coral and sponge gardens in the Aleutian Islands outside of the existing five coral gardens protected by NOAA and the North Pacific Fishery Management Council in 2006.

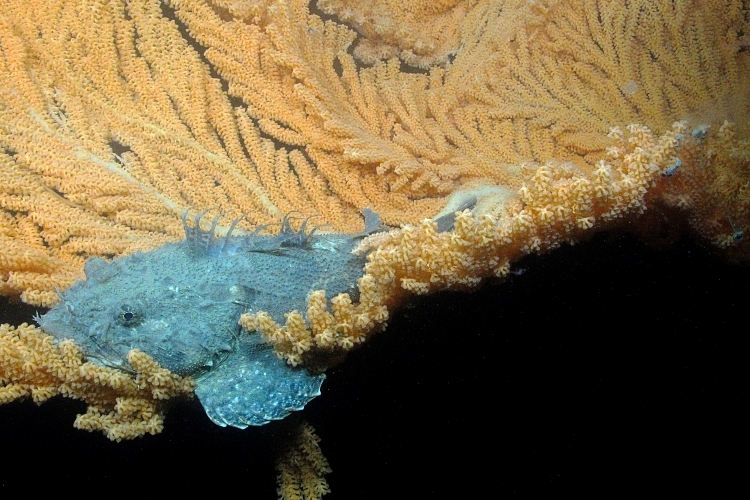

- Improving the understanding of red tree corals (Primnoa pacifica), including the species’ distribution, life history, population connectivity, and potential for recovery from damage in the Gulf of Alaska. Red tree corals are the dominant structure-forming coral species on the outer continental shelf and upper slope between the Alaska Peninsula and the Olympic Coast Marine Sanctuary off Washington State.

- Showing rockfish health and productivity, especially for juveniles and smaller species, were higher in highly structured habitat such as coral and sponge ecosystems than in other types of habitat.

- Publishing 41 peer-reviewed articles and numerous NOAA reports

One of the most important outcomes of the initiative was the production of models of predicted occurrences of corals and sponges for the three major regions of Alaska―the eastern Bering Sea, the Aleutian Islands, and the Gulf of Alaska. Predictive habitat modeling for deep-sea corals and sponges provides an important tool for understanding their distribution across Alaska’s vast geographic regions.

Researchers independently validated models from the eastern Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands using visual surveys. The North Pacific Fishery Management Council used the visual surveys and models for the eastern Bering Sea slope to assess the potential need for additional habitat protections in this region. The findings from the first initiative informed the research priorities of the second initiative, which is taking place between 2020 and 2024.

Explore below for links to regional websites, workshop reports, science plans, expedition reports, and more.

- Alaska Deep-Sea Coral and Sponge Initiative Final Report (2012–2015 Initiative) (NOAA Fisheries; 2017; PDF, 80 pages)

- Deep-Sea Corals and Sponges of Alaska Story Map (NOAA Fisheries)

- Field Guide to Corals of British Columbia, Canada, Alaska, USA, and the eastern North Pacific Ocean (Fisheries and Oceans Canada; 2021; PDF, 136 pages)

- North Pacific Fishery Management Council Website (North Pacific Fisheries Management Council)

- Science Plan for the Second Alaska Deep-Sea Coral and Sponge Initiative (2020-2023) (NOAA Fisheries; 2021)

- State of Deep‐Sea Coral and Sponge Ecosystems of the Alaska Region (2017) (NOAA Fisheries; 2017; PDF, Chapter 3, 37 pages)

- A Guide to the Corals of Alaska (NOAA Fisheries; 2023)

- List of Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the Alaska Region: Depth and Geographic Distribution (v. 2021; PDF, 12 pages)

The first Alaska initiative was made possible by key Program partnerships, many of which have continued into the second initiative. These synergistic efforts have greatly expanded our understanding of the location, ecology, and biology of deep-sea corals and sponges in the region. The U.S. Geological Survey contributed to several facets of this work by providing support for new multibeam backscatter and bathymetry seafloor mapping, digitizing older seafloor survey data, and supporting laboratory coral DNA sequencing to study red tree coral ecology and biology. Scientists from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the University of California Davis also participated in characterizing geology to better understand seafloor habitats. The North Pacific Research Board provided substantial funding for a study on associations between fish and coral habitat in the Gulf of Alaska. NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center provided funding for various initiative projects, a cadre of expert scientists to lead initiative work, and physical facilities to carry out initiative projects that were part of the center’s long-term efforts.

Additionally, a large part of the first Alaska initiative in the Gulf of Alaska was focused on the study of red tree corals due to the importance of this species as habitat. These projects were carried out in partnership with the University of Alaska Fairbanks, The University of Maine, and the Alaska Department of Fish & Game.